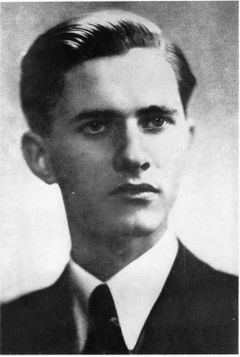

Paul Keres

| Paul Keres | |

|---|---|

| Full name | Paul Keres |

| Country | |

| Born | January 7, 1916 Narva, Estonia, Russian Empire |

| Died | June 5, 1975 (aged 59) Helsinki, Finland |

| Title | Grandmaster |

| Peak rating | 2615 (July 1971) |

- This article uses algebraic notation to describe chess moves.

Paul Keres (January 7, 1916 – June 5, 1975), was an Estonian chess grandmaster.

Keres narrowly missed a chance at a World Chess Championship match on five occasions. He won the 1938 AVRO tournament, which led to negotiations for a World Championship match against Alexander Alekhine, but the match never took place due to World War II. Then after the war he was runner-up in the Candidates' Tournament on four consecutive occasions.

Due to these and other strong results, many commentators consider Keres to be the strongest player never to become World Chess Champion. He was nicknamed "The Crown Prince of Chess".[1]

Early life

Paul Keres was born in Narva, Estonia.

Keres first learned about chess from his father and older brother Harald. With the scarcity of chess literature in his small town, he learned about chess notation from the chess puzzles in the daily newspaper, and compiled a handwritten collection of almost 1000 games.[2] In his early days, he was known for a brilliant and sharp attacking style.[3] He was a three-time Estonian schoolboy champion, in 1930, 1932, and 1933. His playing matured after playing correspondence chess extensively while in high school. He probably played about 500 correspondence games, and, at one time, had 150 correspondence games going at one time. In 1935, he won the International Fernschachbund (IFSB) international correspondence chess championship. From 1937 to 1941 he studied Mathematics at the University of Tartu, and, according to his autobiographical games collection, represented the school in several interuniversity matches.

Pre-war years

Keres became champion of Estonia for the first time in 1935. He tied for first (+5 =1 −2) with Gunnar Friedemann in the tournament, then defeated him (+2 =0 −1) in the playoff match. In April 1935, Keres defeated Feliks Kibbermann, one of Tartu's leading masters, in a training match, by (+3 =0 −1).[4]

Keres played on top board for Estonia in the 6th Chess Olympiad at Warsaw 1935, and was regarded as the new star, admired for his dashing style. His success there gave him the confidence to venture onto the international circuit.

At Helsinki 1935, he placed 2nd behind Paulin Frydman with 6.5/8 (+6 =1 −1). He won at Tallinn 1936 with 9/10 (+8 =2 −0). Keres' first major international success came at Bad Nauheim 1936, where he tied for first with Alexander Alekhine at 6.5/9 (+4 =5 −0). He struggled at Dresden 1936, placing only 8th–9th with (+2 =3 −4), but wrote that he learned an important lesson from this setback. Keres recovered at Zandvoort 1936 with a shared 3rd–4th place (+5 =3 -3). He then defended his Estonian title in 1936 by drawing a challenge match against Paul Felix Schmidt with (+3 =1 −3).[5]

Keres had a series of successes in 1937. He won in Tallinn with 7.5/9 (+6 =3 -0), then shared 1st–2nd at Margate with Reuben Fine at 7.5/9 (+6 =3 −0), 1.5 points ahead of Alekhine. In Ostend, he tied 1st–3rd places with Fine and Henry Grob at 6/9 (+5 =2 -2). Keres dominated in Prague to claim first with 10/11 (+9 =2 -0). He then won a theme tournament in Vienna with 4.5/6 (+4 =1 −1); the tournament saw all games commence with the moves 1.d4 Nf6 2.Nf3 Ne4, known as the Dory Defence. He tied for 4th–5th places in Kemeri with (+8 =7 −2), as Salo Flohr, Vladimirs Petrovs and Samuel Reshevsky won. Then he tied 2nd–4th in Pärnu with 4.5/7 (+3 =3 −1). This successful string earned him an invitation to the tournament at Semmering-Baden 1937, which he won with 9/14 (+6 =6 −2), ahead of Fine, José Raúl Capablanca, Reshevsky, and Erich Eliskases. He was tied for second at Hastings 1937–38 with 6.5/9 (+4 =5 −0) (half a point behind Reshevsky), and at Noordwijk 1938 (behind Eliskases) with 6.5/9 (+4 =5 −0). Keres drew an exhibition match at Stockholm 1938 with Gideon Ståhlberg on 4–4 (+2 =4 −2).[5]

He continued to represent Estonia with success in Olympiad play. His detailed results for Estonia follow.[6]

- Warsaw 1935, Estonia board 1, 12.5/19 (+11 =3 -5);

- Munich 1936 (unofficial Olympiad), Estonia board 1, 15.5/20 (+12 =7 -1), board gold medal;

- Stockholm 1937, Estonia board 1, 11/15 (+9 =4 -2), board silver medal;

- Buenos Aires 1939, Estonia board 1, 14.5/19 (+12 =5 -2), team bronze medal.

World Championship match denied

In 1938 he tied with Fine for first, with 8.5/14, in the all-star AVRO tournament, held in various cities in the Netherlands, ahead of chess legends Mikhail Botvinnik, Max Euwe, Reshevsky, Alekhine, Capablanca and Flohr. AVRO was one of the strongest tournaments in history; some chess historians believe it the strongest ever staged. Keres won on tiebreak because he beat Fine 1½–½ in their individual two games. It was expected that the winner of this tournament would be the challenger for the World Champion title, in a match against World Champion Alexander Alekhine, but the outbreak of the Second World War, especially because of the first occupation of Estonia by the Soviet Union in 1940–1941, brought negotiations with Alekhine to an end. Keres had begun his university studies in 1938, and this also played a role in the failed match. Keres struggled at Leningrad-Moscow 1939 with a shared 12th–13th place; he wrote that he had not had enough time to prepare for this strong event. But he regrouped and won Margate 1939 with 7.5/9 (+6 =3 -0), ahead of Capablanca and Flohr.[5]

World War II

At the outbreak of World War II, Keres was in Buenos Aires at the Olympiad. He stayed on to play in a Buenos Aires International tournament after the Olympiad, and tied for first place with Miguel Najdorf with 8.5/11 (+7 =3 -1).

His next event was a 14-game match with former World Champion Max Euwe in the Netherlands, held from December 1939 – January 1940. Keres managed to win a hard-fought struggle by 7.5–6.5 (+6 =3 -5). This was a superb achievement, because not only was Euwe a former World Champion, but he had enormous experience at match play, far more than Keres.

With the Nazi-Soviet Pact on August 23, 1939, Estonia was occupied by the Soviet Union on 6 August 1940. Keres played in his first Soviet Championship at Moscow 1940 (URS-ch12), placing fourth (+9 =6 -4) in an exceptionally strong field. This was ahead of the defending champion Mikhail Botvinnik, however. The Soviet Chess Federation organized the "Absolute Championship of the USSR" in 1941, with the top six finishers from the 1940 championship meeting each other four times; it was split between Leningrad and Moscow. Botvinnik won this super-strong tournament, one of the strongest ever organized, with 13.5/20, and Keres placed second with 11/20, ahead of Vasily Smyslov, Isaac Boleslavsky, Andor Lilienthal, and Igor Bondarevsky.

With the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941, Estonia came under German control. In 1942–1943 Keres and Alekhine both played in four tournaments organized by Ehrhardt Post, a President of Nazi Grossdeutscher Schachbund. Alekhine won at the Salzburg 1942 chess tournament (Six Grandmasters' Tournament) in June 1942, at Munich (European Individual Chess Championship) in September 1942, and at Prague (International Tournament) in April 1943, always ahead of Keres, who placed second in all three of those tournaments. They tied for first at Salzburg (Six Grandmasters' Tournament) in June 1943, with 7.5/10.

During World War II, Keres played in several more chess tournaments. He won all 15 games at Tallinn 1942 (EST-ch), and swept all five games at Posen 1943. He also won at Tallinn 1943 (EST-ch), and Madrid 1944 (13/14, +12 =2 -0). He was second, behind Stig Lundholm, at Lidköping 1944 (playing hors concours in the Swedish Championship). Keres won a match with Folke Ekström at Stockholm in 1944 by 5–1 (+4 =2 -0).[5]

Dangerous circumstances

The close of World War II placed Keres in dangerous circumstances. During the war, his native Estonia was successively occupied by the Soviets, Germany and again the Soviets. Keres participated in several tournaments in Europe under the German occupation, and when the Soviets occupied Estonia in 1944, he attempted to escape. As a consequence he was harassed by the Soviet authorities and feared for his life. Fortunately, Keres managed to avoid deportation or any worse fate (e.g., that of Vladimirs Petrovs), but his return to the international chess scene was delayed, in spite of his excellent form; he won at Riga 1944/45 (Baltic Championship) (10.5/11). Presumably for political reasons, he was excluded from the ten-player Soviet team for the 1945 radio match against the U.S.A., and he did not participate in the first great post-war tournament at Groningen 1946, which was won by Botvinnik, just ahead of Euwe and Vasily Smyslov.

He won the Estonian Championship at Tallinn 1945 with 13/15 (+11 =4 -0), ahead of several strong visiting Soviets, including Alexander Kotov, Alexander Tolush, Lilienthal, and Flohr. He then won at Tbilisi 1946 (hors concours in the Georgian Championship) with a near-perfect score of 18/19, ahead of Vladas Mikėnas and a 16-year-old Tigran Petrosian.[5]

Keres returned to international play in 1946 in the Soviet radio match against Great Britain, and continued his excellent playing form that year and the next year. Even after he resumed a relatively normal life and chess career, however, his play at the highest level appears to have been affected by living under the enemy occupation of the Soviet Union, which at a minimum must have aggravated the stress of playing under the watchful eye and tight control of the Soviet chess hierarchy.

World Championship Candidate (1948–65)

Although he participated in the 1948 World Championship tournament, arranged to determine the world champion after Alekhine's death in 1946, his performance was far from his best. Held jointly in The Hague and Moscow, the tournament was limited to five participants: Mikhail Botvinnik, Vasily Smyslov, Keres, Samuel Reshevsky, and Max Euwe. (Reuben Fine had also been invited but declined.) The event was played as a quintuple round robin. Keres finished joint third, with 10.5 out of 20 points. In his individual match with the winner, Botvinnik, he lost four of five games, winning only in the last round when the tournament's result was already determined.

Since Keres lost his first four games against Botvinnik in the 1948 tournament, suspicions are sometimes raised that Keres was forced to "throw" games to allow Botvinnik to win the championship. Chess historian Taylor Kingston investigated all the available evidence and arguments, and concluded that: Soviet chess officials gave Keres strong hints that he should not hinder Botvinnik's attempt to win the World Championship; Botvinnik only discovered this about half-way though the tournament and protested so strongly that he angered Soviet officials; Keres probably did not deliberately lose games to Botvinnik or anyone else in the tournament.[7]

Keres finished second or equal second in four straight Candidates' tournaments (1953, 1956, 1959, 1962), making him the player with the most runner-up finishes in that event. (He was therefore occasionally nicknamed "Paul II".) Keres participated in a total of six Candidates' Tournaments:[5]

- Budapest 1950, 4th, behind David Bronstein and Isaac Boleslavsky, with 9.5/18 (+3 =13 -2).

- Zürich 1953, tied 2nd–4th, along with David Bronstein and Reshevsky, two points behind Smyslov, with 16/28 (+8 =16 -4).

- Amsterdam 1956, 2nd, 1.5 points behind Smyslov, with 10/18 (+3 =14 -1).

- Yugoslavia 1959, 2nd, 1.5 points behind Mikhail Tal, with 18.5/28 (+15 =7 -6). He had positive or equal scores against all the competitors, including 3–1 against Tal, but this was not enough, since Tal scored 14.5/16 against the bottom four finishers.

- Curaçao 1962, tied 2nd–3rd, with Efim Geller, half a point behind Tigran Petrosian, with 17/27 (+9 =16 -2). This event is discussed further at World Chess Championship 1963. Keres won a match at Moscow 1962 against Geller, for an exempt place in the 1965 Candidates, by 4.5 – 3.5 (+2 =5 -1).

- Riga 1965, lost his quarter-final match to eventual Candidates' winner Boris Spassky by 6 – 4 (+2 =4 -4). This was the only match loss of Keres' long career.

Keres' run of four successive 2nd places in Candidates' tournaments (1953, 1956, 1959, 1962) has prompted suspicions that he was under orders not to win these events. Taylor Kingston concludes that: there was probably no pressure from Soviet officials, since from 1954 onwards, Keres was rehabilitated and Botvinnik was no longer in favor with officials; at Curaçao in 1962 there was an unofficial conspiracy by Petrosian, Geller and Keres, and this worked out to Keres' disadvantage, since he may have been slightly stronger.[8] Bronstein, in his final book, published just after his death in late 2006, wrote that the Soviet chess leadership favoured Smyslov to win Zurich 1953, and pressured several of the other top Soviets to arrange this outcome, which did in fact occur. Bronstein wrote that Keres was ordered to draw his second cycle game with Smyslov, to conserve Smyslov's fading physical strength; Keres, who still had his own hopes of winning the event, tried as White to win an attacking game, but instead lost because of Smyslov's excellent play.[9]

Three-time Soviet champion, career peak

In several other post-war events, however, Keres dominated the field. He won the exceptionally strong USSR Chess Championship three times. In 1947, he won at Leningrad, URS-ch15, with 14/19 (+10 =8 -1); the field included every top Soviet player except Botvinnik. In 1950, he won at Moscow, URS-ch18, with 11.5/17 (+8 =7 -2) against a field which was only slightly weaker than in 1947. Then in 1951, he triumphed again at Moscow, URS-ch19, with 12/17 (+9 =6 -2),[5] against a super-class field which included Efim Geller, Petrosian, Smyslov, Botvinnik, Yuri Averbakh, David Bronstein, Mark Taimanov, Lev Aronin, Salo Flohr, Igor Bondarevsky, and Alexander Kotov.

Keres won Pärnu 1947 with 9.5/13 (+7 =5 -1), Szczawno-Zdrój 1950 with 14.5/19 (+11 =7 -1), and Budapest 1952 with 12.5/17 (+10 =5 -2),[5] the latter ahead of world champion Botvinnik and an all-star field which included Geller, Smyslov, Gideon Stahlberg, Laszlo Szabo, and Petrosian. The Budapest victory, which capped a stretch of four first-class wins over a two-year span, may represent the peak of his career. The Hungarian master and writer Egon Varnusz, in his books on Keres, states that at this time, "The best player in the world was Paul Keres".[10]

Unmatched International team successes

After being forced to become a Soviet citizen, Keres represented the Soviet Union in seven consecutive Olympiads, winning seven consecutive team gold medals, five board gold medals, and one bronze board medal. His four straight board gold medals is an Olympiad record. Although not selected after 1964, Keres served successfully as a team trainer with Soviet international teams for the next decade. Altogether, in 11 Olympiads (counting the unofficial Munich 1936 event), and in 161 games, Keres accumulated a brilliant total of (+97 =51 -13), for 76.7%. His detailed Soviet Olympiad results are:[11]

- Helsinki 1952, USSR board 1, 6.5/12, team gold;

- Amsterdam 1954, USSR board 4, 13.5/14 (+13 =1 -0), team gold, board gold, best overall score;

- Moscow 1956, USSR board 3, 9.5/12 (+7 =5 -0), team gold, board gold;

- Munich 1958, USSR board 3, 9.5/12 (+7 =5 -0), team gold, board gold;

- Leipzig 1960, USSR board 3, 10.5/13 (+8 =5 -0), team gold, board gold;

- Varna 1962, USSR board 4, 9.5/13 (+6 =7 -0), team gold, board bronze;

- Tel Aviv 1964, USSR board 4, 10/12 (+9 =2 -1), team gold, board gold.

Keres also appeared three times for the Soviet Union in the European Team Championships, winning team and individual gold medals on all three occasions. He scored 14/18 (+10 =8 -0), for 77.8%. His detailed Euroteams results are:[12]

- Vienna 1957, USSR board 2, 3/5 (+1 =4 -0), team gold, board gold;

- Oberhausen 1961, USSR board 3, 6/8 (+4 =4 -0), team gold, board gold;

- Kapfenberg 1970, USSR board 8, 5/5 (+5 =0 -0), team gold, board gold.

Later career

Beginning with the Pärnu 1947 tournament, Keres made some significant contributions as a chess organizer in Estonia; this is an often overlooked aspect of his career.

Keres continued to play exceptionally well on the international circuit. He tied 1st–2nd at Hastings 1954–55 with Smyslov on 7/9 (+6 =2 -1). He dominated an internal Soviet training tournament at Pärnu 1955 with 9.5/10. Keres placed 2nd at the 1955 Göteborg Interzonal, behind David Bronstein, with 13.5/20. Keres defeated Wolfgang Unzicker in a 1956 exhibition match at Hamburg by 6–2 (+4 =4 -0). He tied 2nd–3rd in the USSR Championship, Moscow 1957 (URS-ch24) with 13.5/21 (+8 =11 -2), along with Bronstein, behind Mikhail Tal. Keres won Mar del Plata 1957 (15/17, ahead of Miguel Najdorf), and Santiago 1957 with 6/7, ahead of Alexander Kotov. He won Hastings 1957–58 (7.5/9, ahead of Svetozar Gligorić). He was tied 3rd–4th at Zürich 1959, at 10.5/15, along with Bobby Fischer, behind Tal and Gligoric. He placed tied 7–8th in the URS-ch26 at Tbilisi with 10.5/19, as Petrosian won. Keres was third at Stockholm 1959–60 with 7/9. He won at Pärnu 1960 with 12/15. He was the champion at Zürich 1961 (9/11, ahead of Petrosian). At the elite Bled 1961 event, Keres shared 3rd–5th places, on 12.5/19 (+7 =11 -1), behind only Mikhail Tal and Bobby Fischer.[13] In URS-ch29 at Baku 1961, Keres scored 11/20 for a shared 8–11th place, as Boris Spassky won. Keres shared first with World Champion Tigran Petrosian at the very strong 1963 Piatigorsky Cup in Los Angeles with 8.5/14.[5]

Further tournament championships followed. He won Beverwijk 1964, with 11.5/15, tied with Iivo Nei. He shared first place with World Champion Tigran Petrosian at Buenos Aires 1964, with 12.5/17.[14] He won at Hastings 1964–65 with 8/9. He shared 1st–2nd places at Marianske Lazne 1965 on 11/15 with Vlastimil Hort. In URS-ch33 at Tallinn 1965, he scored 11/19 for 6th place, as Leonid Stein won. He won at Stockholm 1966–67 with 7/9. At Winnipeg 1967, he shared 3rd–4th places on 5.5/9 as Bent Larsen and Klaus Darga won.[5]

At Bamberg 1968, he won with 12/15, two points ahead of World Champion Tigran Petrosian. He was 2nd at Luhacovice 1969 with 10.5/15, behind Viktor Korchnoi. At Tallinn 1969, he shared 2nd–3rd places on 9/13 as Stein won. At Wijk aan Zee 1969, he shared 3rd–4th places on 10.5/15, as Geller and Botvinnik won. He won Budapest 1970 with 10/15, ahead of Laszlo Szabo. Also in 1970, Keres's 3:1 with Ivkov on the tenth board gave victory to the Soviet team in the match vs Rest of the World. He shared 1st–2nd at Tallinn 1971 with Mikhail Tal on 11.5/15. He shared 2nd–3rd at Parnu 1971, on 9.5/13, as Stein won. He shared 2nd–4th at Amsterdam 1971 with 9/13, as Smyslov won. He shared 3rd–5th places at Sarajevo 1972 on 9.5/15, as Szabo won. He placed 5th at San Antonio 1972 on 9.5/15, as Petrosian, Lajos Portisch, and Anatoly Karpov won.[5]

At Tallinn 1973, he shared 3rd–6th places on 9/15, as Mikhail Tal won. His last Interzonal was Petropolis 1973, where he scored 8/17 for a shared 12–13th place, as Henrique Mecking won. That same year, he made his last Soviet Championship appearance, at Moscow for URS-ch41, scoring 8/17 for a shared 9–12th place, as Boris Spassky won.

Death

His health declined the next year, and he did not play any major events in 1974. Keres' last major tournament win was Tallinn 1975, just a few months before his death.[15]

He died of a heart attack in Helsinki, Finland, at the age of 59 (it is commonly reported that he died on the same date in Vancouver, Canada). His death occurred while returning to his native Estonia from a tournament in Vancouver, which he had won.[5] The Paul Keres Memorial Tournaments have been held annually mainly in Vancouver and Tallinn ever since.

Over 100,000 were in attendance at his state funeral in Tallinn, Estonia, where the leaders of Estonia were on guard of honour, and FIDE President Max Euwe, his old friend and rival, was also present.[16]

Chess legacy and writings

The unofficial Chessmetrics system places Keres in the top 10 players in the world between approximately 1936 and 1965, and overall he had one of the highest winning percentages of all grandmasters in history. He has the seventh highest Chessmetrics 20-year average, from 1944 to 1963.

He was one of the very few players who had a plus record against Capablanca. He also had plus records against World Champions Euwe and Tal, and equal records against Smyslov, Petrosian and Anatoly Karpov. In his long career, he played no fewer than ten world champions. He beat every world champion from Capablanca through Bobby Fischer (his two games with Karpov were drawn), making him the only player ever to beat nine undisputed world champions. Other notable grandmasters against whom he had plus records include Fine, Flohr, Viktor Korchnoi, Efim Geller, Savielly Tartakower, Mark Taimanov, Milan Vidmar, Svetozar Gligorić, Isaac Boleslavsky, Efim Bogoljubov and Bent Larsen.

He wrote a number of chess books, including a well-regarded, deeply annotated collection of his best games, Grandmaster of Chess ISBN 0-668-02645-6, The Art of the Middle Game (with Alexander Kotov) ISBN 0-486-26154-9, and Practical Chess Endings ISBN 0-7134-4210-7. All three books are still considered among the best of their kind for aspiring masters and experts. He also wrote several tournament books, including an important account of the 1948 World Championship Match Tournament. He authored several openings treatises, often originally in German, as listed by the Hungarian writer Egon Varnusz: Spanisch bis Franzosisch, Dreispringer bis Konigsgambit, and Vierspringer bis Spanisch. He contributed to the first volume, 'C', of the first edition of the Yugoslav-published Encyclopedia of Chess Openings (ECO), which appeared in 1974, just before his death the next year. Keres also co-founded the Riga magazine Shakhmaty.

Keres made many important contributions to opening theory. Perhaps best-known is the Keres Attack against the Scheveningen Variation of the Sicilian Defence (1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 e6 6.g4), which was successfully introduced against Bogolyubov at Salzburg 1943, and today remains a topical and important line. An original system on the Black side of the Closed Ruy Lopez (1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.Bb5 a6 4.Ba4 Nf6 5.0-0 Be7 6.Re1 b5 7.Bb3 d6 8.c3 0-0 9.h3 Na5 10.Bc2 c5 11.d4 Nd7) was introduced by Keres at the 1962 Candidates' tournament, and it had a run of popularity for several years. He also popularized the Keres Defence (1.d4 e6 2.c4 Bb4+). Another important system on the Black side of the English Opening was worked out by him; it runs 1.c4 e5 2.Nc3 Nf6 3.g3 c6.

The Hungarian writer Egon Varnusz wrote that Keres "published 180 problems and 30 studies. One of his rook endings won first prize in 1947."[17]

Keres won top-class tournaments from the 1930s into the 1970s, a span of nearly 40 years, and won events in western Europe, eastern Europe, the Soviet Union, South America, and North America. Botvinnik, by contrast, never competed in the Americas during his career.

His rival Samuel Reshevsky, while paying tribute to Keres' talent, tried to pinpoint why Keres never became world champion, and also complimented his friendly personality. "Well, I believe that Keres failed in this respect because he lacked the killer instinct. He was too mild a person to give his all in order to defeat his opponents. He took everything, including his chess, philosophically. Keres is one of the nicest people that I have ever had the pleasure of meeting. With his friendly and sincere smile, he makes friends easily. He is goodnatured and kind. Yes, he loves chess, but being a human being is his first consideration. In addition to chess, Keres is interested in tennis, Ping-Pong, swimming, and bridge."[18]

Acknowledgements

The five kroons (5 krooni) Estonian banknote bears his portrait. He is the only chess player whose portrait is on a banknote.[19]

A statue honouring him can be found on Tõnismägi in Tallinn.

An annual international chess tournament has been held in Tallinn every other year since 1969. Keres won this tournament in 1971 and 1975. Starting in 1976 after Keres' death, it has been called the Paul Keres Memorial Tournament. There are also the annual Keres Memorial tournament held in Vancouver[20] and a number of chess clubs and festivals named after him.

In 2000, Keres was elected the Estonian Sportsman of the Century.

There is also a street in Nõmme, a district of Tallinn, which was named after Keres.

Notable chess games

- Paul Keres vs Alexander Alekhine, Margate 1937, Ruy Lopez (C71), 1-0 Here Keres outplayed Alekhine already in the first 15 moves. The game is crowned by two small combinations.

- Paul Keres vs José Raúl Capablanca, AVRO Amsterdam 1938, French, Tarrasch, Open Variation, Main line (C09), 1-0 Almost unpredictable jumps of the White Knight slowly destroy Black's position. A beautiful tactical game.

- Max Euwe vs Paul Keres, Amsterdam 1940 (match), Queen's Indian, Old Main line (E19), 0-1

- Paul Keres vs Jaroslav Šajtar, Amsterdam 1954 (ol), Sicilian, Najdorf (B94), 1-0 A typical Sicilian sacrifice on e6.

- Paul Keres vs Mikhail Botvinnik, Moscow 1956 (Alekhine Memorial), Sicilian, Richter-Rauzer Attack (B63), 1-0

- Paul Keres vs Edgar Walther, Tel Aviv 1964, King's Indian, Petrosian System (E93), 1-0 The game where Keres introduced a new plan against the King's Indian opening: Bg5, h4, Nh2 and a sacrifice on g4.

Quotes

- "At Amsterdam in 1954 he scored 96.4% on fourth board and won another game so brilliant against Šajtar of Czechoslovakia that the Soviet non-playing captain, Kotov, told to me that it was 'a true Soviet game.' I told this to Keres who, with the nearest approach to acerbity I ever saw him show, said: 'No, it was a true Estonian game.'" – Grandmaster Harry Golombek

- "At the Warsaw team tournament in 1935, the most surprising discovery was a gangling, shy, 19-year-old Estonian. Some had never heard of his country before, nobody had ever heard of Keres. But his play at top board was a wonder to behold. Not merely because he performed creditably in his first serious encounters with the world's greatest; others have done that too. It was his originality, verve, and brilliance which astounded and delighted the chess world." – Grandmaster Reuben Fine

- "I loved Paul Petrovitch with a kind of special, filial feeling. Honesty, correctness, discipline, diligence, astonishing modesty – these were the characteristics that caught the eye of the people who came into contact with Keres during his lifetime. But there was also something mysterious about him. I had an acute feeling that Keres was carrying some kind of a heavy burden all through his life. Now I understand that this burden was the infinite love for the land of his ancestors, an attempt to endure all the ordeals, to have full responsibility for his every step. I have never met a person with an equal sense of responsibility. This man with internally free and independent character was at the same time a very well disciplined person. Back then I did not realise that it is discipline that largely determines internal freedom. For me, Paul Keres was the last Mohican, the carrier of the best traditions of classical chess and – if I could put it this way – the Pope of chess. Why did he not become the champion? I know it from personal experience that in order to reach the top, a person is thinking solely of the goal, he has to forget everything else in this world, toss aside everything unnecessary – or else you are doomed. How could Keres forget everything else?" – Former World Champion Boris Spassky[21]

- "I was unlucky, like my country." – Paul Keres, on why he never became world champion.[22]

Books

- Keres, Paul; Kotov, Alexander (1964). The Art of the Middle Game. Penguin Books

- Keres, Paul (1984). Practical Chess Endings. Batsford. ISBN 0-7134-4210-7

Tournament and match record

Keres' tournament and match record:[15][23]

Tournaments

-

Year Tournament Place Notes 1935 6th Olympiad – +11−5=3 on first board for Estonia 1935 Helsinki 2 Frydman won 1936 Nauheim 1–2 shared 1–2 with Alekhine 1936 Dresden 8–9 Alekhine won 1936 Zandvoort 3–4 Fine won 1937 Margate 1–2 shared 1–2 with Fine 1937 Ostend 1–3 shared 1–3 with Grob and Fine 1937 Prague 1 ahead of Zinner 1937 Vienna 1 Quadrangular 1937 Kemeri 4–5 Reshevsky, Flohr, and Petrovs shared 1st–3rd 1937 Pärnu 2–4 Schmidt won 1937 7th Olympiad – individual silver (+9−2=4) on first board for Estonia 1937 Semmering/Baden 1 ahead of Fine 1937/38 Hastings 2–3 Reshevsky won 1938 Noordwijk 2 Eliskases won 1938 AVRO 1–2 shared 1–2 with Fine, ahead of Botvinnik 1939 Leningrad-Moscow 12–13 Flohr won 1939 Margate 1 ahead of Capablanca and Flohr 1939 8th Olympiad – +12−2=5 on first board for bronze medal winning Estonia 1939 Buenos Aires 1–2 shared 1–2 with Najdorf 1940 12th USSR Championship 4 Lilienthal and Bondarevsky won 1941 Absolute USSR Championship 2 behind Botvinnik 1942 Tallinn 1 Estonian Championship +15−0=0 1942 Salzburg 2 behind Alekhine 1942 Munich 2 "European Championship", behind Alekhine 1943 Prague 2 behind Alekhine 1943 Poznań 1 ahead of Grünfeld 1943 Salzburg 1–2 shared 1–2 with Alekhine 1943 Tallinn 1 Estonian Championship +6−1=4 1943 Madrid 1 1944 Lidköping 2 Swedish Championship 1944/45 Riga 1 Baltic Championship 1946 Tbilisi 1 Georgian Championship 1947 Pärnu 1 1947 15th USSR Championship 1 1947 Moscow 6–7 1948 World Championship Tournament 3–4 Botvinnik 1st, Smyslov 2nd 1949 17th USSR Championship 8 1950 Budapest 4 Candidates Tournament, Bronstein and Boleslavsky 1st–2nd, Smyslov 3rd 1950 Szczawno-Zdrój 1 1950 18th USSR Championship 1 1951 19th USSR Championship 1 1952 20th USSR Championship 10–11 Botvinnik won 1952 Budapest 1 1952 10th Olympiad – +3−2=7 on first board for gold medal USSR team 1953 Zürich 2–4 Candidates Tournament, Smyslov 1st 1954 11th Olympiad – individual gold (+13−0=1) on fourth board for gold medal USSR team 1954/55 Hastings 1–2 shared 1–2 with Smyslov 1955 22nd USSR Championship 7–8 Geller won 1955 Göteborg 2 Interzonal, Bronstein won 1956 Amsterdam 2 Candidates Tournament, Smyslov won 1956 12th Olympiad – individual gold (+7−0=5) on third board for gold medal USSR team 1956 Moscow 7–8 1957 24th USSR Championship 2–3 Tal won 1957 Mar del Plata 1 1957 Santiago 1 1957/58 Hastings 1 1958 13th Olympiad – individual gold (+7−0=5) on third board for gold medal USSR team 1959 26th USSR Championship 7–8 Petrosian won 1959 Zürich 3–4 Tal won 1959 Bled/Belgrade/Zagreb 2 Candidates Tournament, Tal won 1959/60 Stockholm 3 1960 14th Olympiad – individual gold (+8−0=5) on third board for gold medal USSR team 1961 Zürich 1 1961 Bled 3–5 Tal won 1961 29th USSR Championship 8–11 1962 Curaçao 2–3 1962 Candidates Tournament, Petrosian won 1962 15th Olympiad − individual bronze (+6−0=7) on fourth board on gold medal USSR team 1963 Los Angeles 1–2 1st Piatigorsky Cup, tied with Petrosian for first 1964 Beverwijk 1–2 Hoogovens tournament, shared 1–2 with Nei 1964 Buenos Aires 1–2 shared 1–2 with Petrosian 1964 16th Olympiad − individual gold (+9−1=2) on fourth board for gold medal USSR team 1964/65 Hastings 1 1965 Mariánské Lázně 1–2 shared 1–2 with Hort 1965 33rd USSR Championship 6 Stein won 1966/67 Stockholm 1 1967 Moscow 9–12 1967 Winnipeg 3–4 1968 Bamberg 1 1969 Beverwijk 3–4 Hoogovens tournament, behind Botvinnik and Geller 1969 Tallinn 2–3 1970 Budapest 1 1971 Amsterdam 2–4 1971 Pärnu 2–3 1971 Tallinn 3–6 1972 Sarajevo 3–5 1972 San Antonio 5 Karpov, Petrosian, and Portisch shared 1st–3rd 1973 Tallinn 3–6 1973 Dortmund 6–7 1973 Petropolis 12–13 Interzonal, Mecking 1st; Geller, Polugaevsky, and Portisch 2nd–4th 1973 41st USSR Championship 9–12 Spassky won 1975 Tallinn 1 1975 Vancouver 1

Matches

-

Year Opponent Result 1935 Gunnar Friedemann +2 −1 =0 1935 Feliks Kibbermann +3 −1 =0 1936 Paul Felix Schmidt +3 −3 =1 1938 Gideon Ståhlberg +2 −2 =4 1939/40 Max Euwe +6 −5 =3 1944 Folke Ekström +4 −0 =2 1956 Wolfgang Unzicker +4 −0 =4 1962 Efim Geller +2 −1 =5 1965 Boris Spassky +2 −4 =4 1970 Borislav Ivkov +2 −0 =2

Scores against other outstanding Grandmasters

Only official tournament or match games are accounted for.

|

|

|

|

| Awards and achievements | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Uno Palu |

Estonian Sportspersonality of the Year 1959 |

Succeeded by Hanno Selg |

| Preceded by Toomas Leius |

Estonian Sportspersonality of the Year 1962 |

Succeeded by Toomas Leius |

Notes

- ↑ David Hooper, Ken Whyld, Kenneth Whyld, The Oxford Companion to Chess, Oxford University Press 1992, page 198

- ↑ Paul Keres, Grandmaster of Chess: The Complete Games of Paul Keres, ed. and trans. by Harry Golombek, Arco, New York, 1977.

- ↑ "Paul Keres". Zone.ee. http://www.zone.ee/pkeres/partiid.php. Retrieved 2008-10-26.

- ↑ Grandmaster of Chess, by Paul Keres, Arco 1972, pp 188–189

- ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 5.11 http://www.chessmetrics.com, the Paul Keres results file

- ↑ http://www.olimpbase.org/players/cq6agwkb.html (1935, 1937, 1939 results); Grandmaster of Chess, by Paul Keres, Arco 1972, p. 188 (1936 results)

- ↑ Kingston wrote a 2-part series: Kingston, T. (1998). "The Keres-Botvinnik Case: A Survey of the Evidence – Part I". The Chess Cafe. http://www.chesscafe.com/text/kb1.txt. and Kingston, T. (1998). "The Keres-Botvinnik Case: A Survey of the Evidence – Part II". The Chess Cafe. http://www.chesscafe.com/text/kb2.txt. Kingston published a further article, Kingston, T. (2001). "The Keres-Botvinnik Case Revisited: A Further Survey of the Evidence" (PDF). The Chess Cafe. http://www.chesscafe.com/text/skittles165.pdf. after the publication of further evidence which he summarizes in his third article. In a subsequent 2-part interview with Kingston, Soviet grandmaster and official Yuri Averbakh said that: Stalin would not have given orders that Keres should lose to Botvinnik; Smyslov would probably have been the candidate most preferred by officials; Keres was under severe psychological stress as a result of the multiple invasions of his home country, Estonia, and of his subsequent treatment by Soviet officials up to late 1946; and Keres was less tough mentally than his rivals – Kingston, T. (2002). "Yuri Averbakh: An Interview with History – Part 1" (PDF). The Chess Cafe. http://www.chesscafe.com/text/skittles181.pdf. and Kingston, T. (2002). "Yuri Averbakh: An Interview with History – Part 2" (PDF). The Chess Cafe. http://www.chesscafe.com/text/skittles183.pdf.

- ↑ Kingston, T. (2001). "The Keres-Botvinnik Case Revisited: A Further Survey of the Evidence" (PDF). The Chess Cafe. http://www.chesscafe.com/text/skittles165.pdf.

- ↑ Secret Notes, by David Bronstein and Sergey Voronkov, Edition Olms, Zurich 2007

- ↑ Paul Keres' Best Games, Volume I: Closed Games, by Egon Varnusz, Cadogan Chess, London 1987, p.xii

- ↑ Men's Chess Olympiads :: Paul Keres. OlimpBase. Retrieved on 2009-11-06.

- ↑ European Men's Team Chess Championship :: Paul Keres. OlimpBase. Retrieved on 2009-11-06.

- ↑ "BLED 1961". Thechesslibrary.com. http://www.thechesslibrary.com/files/1961Bled.htm. Retrieved 2008-10-26.

- ↑ "BAIRES64". Thechesslibrary.com. http://www.thechesslibrary.com/files/1964BuenosAires.htm. Retrieved 2008-10-26.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 "Paul Keres". Zone.ee. http://www.zone.ee/pkeres/karjaar.php. Retrieved 2008-10-26.

- ↑ Paul Keres' Best Games, Volume I: Closed Games, by Egon Varnusz, Cadogan Chess 1987, p. xiii

- ↑ Paul Keres' Best Games, Volume 1: Closed Games, by Egon Varnusz, London, Cadogan 1987

- ↑ Great Chess Upsets, by Samuel Reshevsky, Arco Publishing, New York 1976, p. 185.

- ↑ "ChessBase.com – Chess News – Remembering Paul Keres". Chessbase.com. http://www.chessbase.com/newsdetail.asp?newsid=983. Retrieved 2008-10-26.

- ↑ "Keres Memorial History Summary". Keresmemorial.chessbc.ca. http://keresmemorial.chessbc.ca/KeresMemorialSummary.html. Retrieved 2008-10-26.

- ↑ "Noteworthy Estonians – PAUL KERES – Chess player". http://www.vm.ee/est/kat_29/3921.html.

- ↑ Remembering Paul Keres, Chessbase, 3-6-2003

- ↑ Bisguier, Arthur. "Paul Keres, 1916–1975". Chess Life & Review December 1975. Reprinted in Pandolfini, Bruce, ed (1988). The Best of Chess Life and Review, Volume 2, 1960–1980. Simon and Schuster. pp. 352–353. ISBN 0-671-66175-2

References

- Keres, Paul; Harry Golombek (ed. and trans.). Grandmaster of Chess: The Complete Games of Paul Keres. Arco, New York, 1977.

- Varnusz, Egon. Paul Keres' Best Games, Volume 1: Closed Games. Cadogan Chess, London, 1994, ISBN 1-85744-064-1.

- Paul Keres Best Games, Volume II: Semi-Open Games, by Egon Varnusz, London 1994, Cadogan Chess, ISBN 0-08-037139-6.

- Paul Keres: der Komponist = the Composer, by Alexander Hildebrand, F. Chlubna, Vienna, 1999.

External links

- Paul Keres player profile at ChessGames.com

- Estonian banknotes

- Paul Keres at www.chesslady.com (in Czech)

- 6 studies of Paul Keres